CityCouncil3

Newton City Council Chambers. Photo by Bryan McGonigle

The City Council passed the Village Center Overlay District rezoning plan last week, but not before a slew of amendments were adopted, many of which scaled back the ambitious proposal.

“I’m really pleased that the ordinance was passed pretty much intact—not many changes to the text,” Councilor Deb Crossley, chair of the Zoning and Planning Committee since 2020, said. “But dramatic changes to the map.”

The basic concept of the plan—three new higher-density zones added to village centers to foster more housing there in the future—made it through approval. The amendments were mostly aimed at moving specific parcels to lower-density zones than the plan had them in or removing those parcels from the VCOD altogether.

So what’s in the plan that passed? What was cut? And what does it all mean?

Dropping six

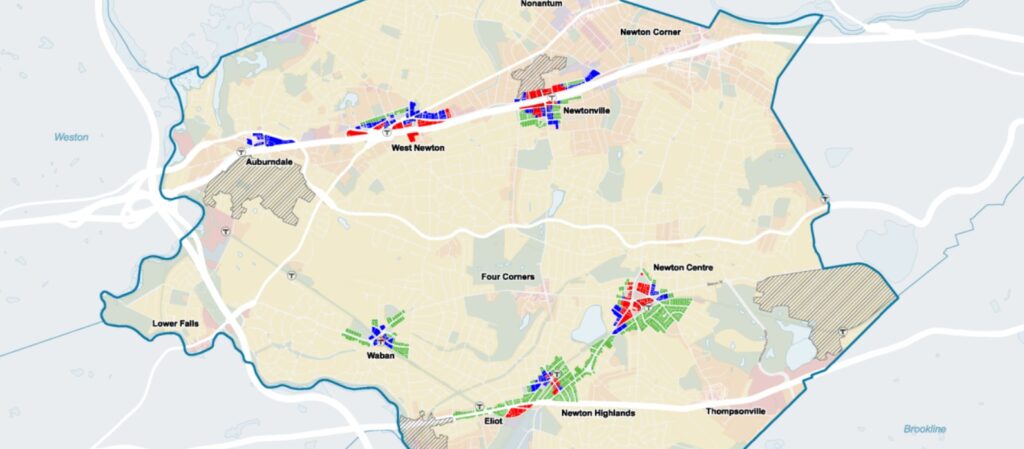

The biggest change to the map came during the second night of debate, when Councilor Pam Wright proposed an amendment removing six villages— Newton Lower Falls, Newton Upper Falls, Thompsonville, Four Corners, Newton Corner and Nonantum—from the Village Center Overlay District.

Wright offered the amendment because those villages don’t count toward MBTA Communities Act compliance. The Council passed Wright’s amendment as a compromise between supporters and opponents of the VCOD that still allowed the VCOD to satisfy the requirements of the MBTA Communities Act.

Then, councilors offered amendments to change parcels in the remaining villages from the VC3 zone, which allows 4 ½ story buildings by right, to VC2, which allows for 3 ½ stories by right.

“We eliminated six villages, then we went surgically from one village to the next, which we’d already done several times in committee, and the opposition kept hammering on their perceived need to reduce the unit count to get much closer to the MBTA Communities compliance formula count,” Crossley said.

Many of the lots down-zoned from VC3 to VC2 in the amendments process were in in the cores of four villages, with the majority in West Newton. Other areas with down-zoned village center lots include Lincoln Street in Newton Highlands and Walnut Street in Newtonville.

And the final version of the VCOD includes parking requirements for the highest-density zone, VC3.

Marc Laredo, a longtime critic of the VCOD plan who will serve as president of the City Council starting in January, said he wasn’t opposed to the idea of rezoning the village centers and that he and every other councilor wants to comply with state law.

Laredo and several others who had opposed the scale of the VCOD ended up voting for it after the amendments cut several villages and trimmed the highest density zoning out of several of the remaining village centers.

“The scaled back version that we passed I think in large part reflected the will of the voters that we comply with the MBTA Communities Act but not go further,” Laredo said.

About Auburndale

The plan did go beyond the MBTA Communities Act, though. Auburndale was included in the VCOD because the Auburndale commuter rail station dramatically needs renovations, the funding for which could be in jeopardy if that part of the city is not included in the rezoning plan.

Newton has three commuter rail stations, and all three need improvements for accessibility. And the Newton-Auburndale station only has a platform on one side, impeding the MBTA’s ability to offer a full day of train trips on its schedule.

“Unlike our neighbors in Wellesley and other communities along the same route, Newton essentially has service going into Boston only in the morning and service back to Newton only in the afternoon,” Mayor Ruthanne Fuller wrote in a statement in November urging Auburndale be kept in the VCOD plan.

The state may fund a portion of the $200 million tab for the improvements to Newton’s commuter rail stations. But excluding Auburndale from a plan to increase housing near the commuter rail—a top priority of Gov. Maura Healey—could result in the state refusing that funding.

“I certainly hope that we actually get that funding,” Laredo said. “It has been discussed now for many years.”

If the state fixes the problems with the stations along with other issues the MBTA faces, Laredo added, rezoning for high density housing would be an easier sell to the public.

“I think that for truly transit-oriented housing to work, you have to have excellent transit,” Laredo said. “And if you have excellent transit, you’ll have an easier time persuading people that transit-oriented housing is going to be effective. And right now, I don’t think anyone in the commonwealth thinks that our transit is where it should be.”

And after some controversy over flooding caused by an old erroneously placed pipe, Border Street was added back into the rezoning plan.

‘Phantom units’

Despite months of heated debate and an election focused solely on the rezoning plan, the Council had consensus on one thing: the desire to comply with the MBTA Communities Act.

That new state law mandates that cities and towns with MBTA stops must up-zone the neighborhoods around those MBTA stops for higher density housing.

The law uses a formula to determine how much housing potential each community has to account for in their zoning plans, and in Newton, that number is 8,330 potential housing units.

After amendments scaled the plan down, the total potential unit count is around 8,700.

But what do the numbers actually mean? Not much, as it turns out.

“Unit capacity does not equal units,” Crossley said during the Nov. 29 zoning debate. “They’re not real units.”

Newton is already developed, Crossley noted at that meeting, so there’s not much room for developers to add new buildings. The zoning plan is about redevelopment of already built-on parcels.

“The unit capacity numbers dramatically overcount what real potential units could even possibly physically be,” Crossley said.

The MBTA Communities Act, for example, uses small unit sizes and does not subtract what is already built from what can be built. A newly built development like the Trio apartment building on Washington Street isn’t likely to be torn down and rebuilt.

And then there are the churches. During the debate process, councilors offered amendments to down-zone parcels with churches on them. But the Council included them in up-zoning, so that the landowners could develop other parts of the lots if they wanted. So the whole parcel is up-zoned for housing units, while in reality the part where the church is standing won’t be built up to the new zoning capacity.

Crossley said she thinks councilors who sought to down-zone village center lots or remove streets from the rezoning plan are afraid of allowing more housing.

“They’re trying to reduce the housing potential. That’s really what they’re doing,” Crossley said. “And they’re scaring people with the numbers, but the numbers only comes from a compliance formula. They are totally not real numbers.”

Councilor Alison Leary had similar sentiment during the Council’s Nov. 29 meeting, calling the numbers “essentially meaningless.”

“To get those numbers [of units built] that the MBTA Communities Act requires [for zoning] would mean bulldozing 50 acres of buildings, because we’re almost all built out, and build all 800-to-1,000-square-foot units will no parking, and that is not very likely,” Leary said. “And I’ve always been kind of surprised. Why does everyone care so much about these phantom units?”

Laredo agreed that the unit counts don’t mean actual units and only reflect a hypothetical compliance formula, but he said using the numbers as a guide was a means of navigating that compliance.

“I am assuming the state knew what it was doing when it set those formulas and created those numbers, and the state made certain assumptions and then crafted rules based on those assumptions,” Laredo said. “I don’t think anybody has ever suggested that we are, in the next 20 years, going to build out the maximum number of units within this corridor.”

Laredo said he wanted the rezoning process to come with estimates on what is likely to be built in the next several years along with what’s already approved and make a plan based on that information and the resources the city has.

“There’s not a right or wrong answer to that, but there’s a planning answer,” Laredo said.

Jen Caira, Newton’s deputy planning director, said the MBTA Communities Act numbers are just guidance used to determine compliance and not meant to be taken as exact unit counts in various communities in which the law applies.

“It’s really really looking at the max number of units that can go somewhere,” Caira said. “So it’s not a realistic buildout and doesn’t account for anything that’s already there.”

The MBTA numbers relate to reality kind of like the computer game SimCity. The MBTA Communities Act number would only work on a fresh new game with nothing built yet, and Newton is like a game someone has played for a week and has built on almost every inch of landscape.

There are currently building projects in various stages of development, but those are not being counted toward MBTA Communities Act compliance.

The feasibility factor

The Council passed the ordinance—cut back and scaled down, but in compliance with the state formula nonetheless—but the state still has to greenlight it.

The city has commissioned a feasibility analysis to be sent to the state to make sure it can work financially in the real world.

“They are looking at anywhere where we’re requiring affordable housing,” Caira said. “Where we’re concerned and what I raised at Council as well is the VC2 mixed-use.”

The VC2 lots are only allowed to be built up to 3 ½ stories by right, and having ground floor retail would mean a maximum of 2 ½ stories of residential, which may not be enough to make a building financially sustainable if there are affordable housing requirements as well.

Crossley said she fears the plan may have been scaled back so much that it’s “dangerously close” to the bare minimum required and that the city has to be careful since both MBTA compliance and the city’s inclusionary zoning that requires housing above retail could be in jeopardy if the rezoning doesn’t pass the feasibility test.

A certain amount of housing is needed above retail space in order for the housing to offset costs associated with the retail, Crossley continued. So decreasing the number of potential units above the first-floor retail—while maintaining the MBTA Communities Act compliance—could lead the state to consider the whole parcel’s zoning to be financially unfeasible.

And while decreasing potential units on a lot may appease opponents of the rezoning plan, it could also cost the city the feasibility determination and, therefore, the city’s MBTA compliance and inclusionary zoning policy.

“No developer of affordable housing is anywhere telling us that they can put 2 ½ stories [of housing] on top of a story of retail and make it pencil out,” Crossley said.

Laredo said he hopes the VCOD plan the Council passed will make it through the feasibility test, but if it doesn’t the Council can make adjustments to it.

“We want to comply,” Laredo said. “We are acting in good faith. Everybody is acting in good faith. And the state is acting in good faith.”