forum2

During a panel discussion at the Charles River Chamber forum on housing and the economy, Tiffany Chen talks about the difficulties of finding housing she can afford in Greater Boston. With her are William Ferreira, left, and Michaela DeSantis, right. Photo by Bryan McGonigle

PHOTO: During a panel discussion at the Charles River Chamber forum on housing and the economy, Tiffany Chen talks about the difficulties of finding housing she can afford in Greater Boston. With her are William Ferreira, left, and Michaela DeSantis, right. Photo by Bryan McGonigle

Why is Newton losing its young adult population?

The Charles River Regional Chamber hosted a forum at the UMass Mt. Ida campus on Wednesday, titled “The Road Ahead,” hoping to answer that question and discuss possible solutions to the exodus of youth that has accompanied the housing crisis of the past several years.

Massachusetts is a net-loser

Massachusetts is losing residents. An analysis of outmigration published by Boston Indicators in April shows that despite overall population increasing in Massachusetts over the past couple of decades, the rate of people moving away has accelerated.

“Were it not for offsetting growth from international migration, we’d have been losing population for years,” the Boston Indicators report reads. “In fact, we’ve recently seen domestic outmigration outpace international in-migration, and our overall population shrank in 2021 and 2022 for the first time in years.”

And population growth has slowed in comparison to the rest of the country to the point that after both the 2010 and 2020 census, Massachusetts lost congressional seats.

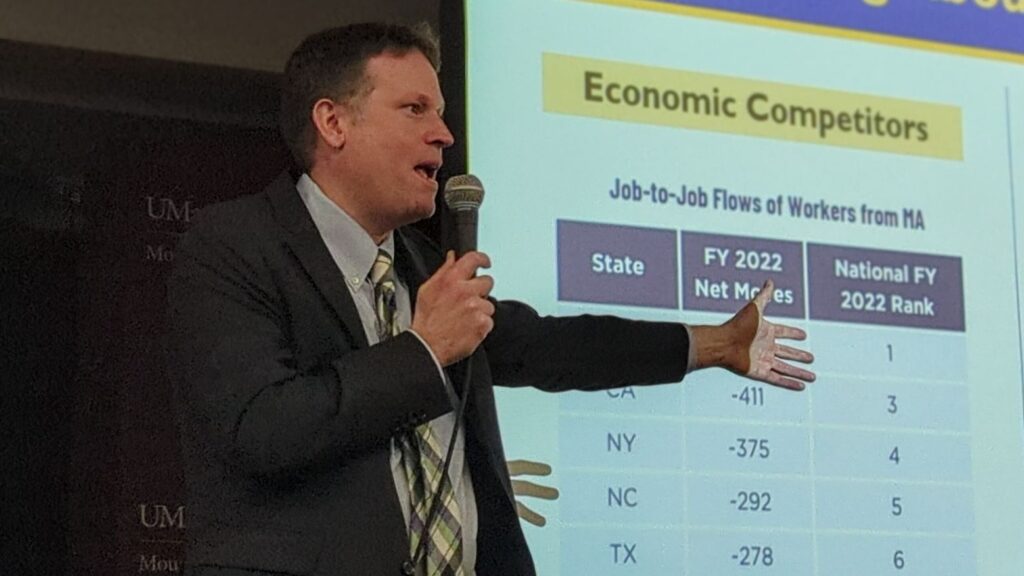

As it turns out, Massachusetts has a long history of people leaving for other parts of the country and being replaced by immigrants, Massachusetts Taxpayer Foundation President Doug Howgate said at Wednesday’s forum.

“For 400 years, Massachusetts has been a domestic migration net-loser,” Howgate said.

While that’s not new, what is new is the reason.

In both the early 1990s and early 2000s, Massachusetts had outmigration surges related to recessions at those times—national recessions that hit the Bay State harder than other part of the country—because people were leaving to find jobs.

But Massachusetts’ economy is doing well now, Howgate noted, while still seeing a surge in outmigration.

“We have two job openings for every applicant,” he said. “That’s not the issue. Something else is going on. Something else is causing folks to leave, maybe because they can’t afford to live here or because they can afford to look for better options.”

The pandemic flip

One of the options opened up by the COVID-19 pandemic was remote work. A lot of people no longer had to drive to and from an office, so they were no longer tethered to a specific location.

And some people took advantage of that by moving to less expensive areas while keeping their jobs based in the Boston area and eastern Massachusetts.

“Patterns that were in place pre-pandemic were flipped on their heads,” Howgate said.

Suddenly eastern Massachusetts—the part of the state that has tended to see the most in-migration—is seeing the highest rate of outmigration, with Middlesex and Suffolk County seeing the sharpest increases in people leaving.

“That is absolutely a mirror image of what you would have seen in 2018,” Howgate said.

Meanwhile, counties farther away from Greater Boston have seen an increase in new residents. The biggest increase was seen in Cape Cod.

“Cape Cod,” Howgate marveled. “That hasn’t been true since 1620.”

Gone are the days when everyone who wanted to work in Boston had to live in or around the Boston area.

But rent and home prices in the region—particularly along the 95 corridor where Newton sits—have skyrocketed.

And those factors are likely behind the exodus of young adults from Newton and the rest of Greater Boston. So the region and the state need to get competitive to attract young adults.

“The bottom line is we have a super educated workforce, that educated work force has a positive feedback loop with economic sectors, but we’re really expensive,” Howgate said.

The struggle is real

Newton’s population is getting older. Nearly a quarter of the city’s population is over the age of 65, higher than the state average of 18 percent. And demographic forecasts show seniors’ share of the city’s population increasing greatly over the next several years, as more empty-nesters stay in their houses without reasonable housing options to downsize to and more young people look elsewhere to start their families.

Wednesday’s forum included two panel discussions, the first of which was moderated by Chamber Public Policy & Government Affairs Manager Max Woolf and included several young professionals affected by the rise in housing prices in the region.

Tiffany Chen, a senior account manager with MORE Advertising, grew up in Newton and, after moving back to the area after college, has been living with her family in Weymouth while paying off her college debt. And she’s still having trouble finding an apartment in Greater Boston that she can afford.

“Living in Weymouth, my commute is an hour and 15 minutes on average—just one way, traveling 24 miles—and that can be a lot,” Chen said.

She works from home a lot, but as a young professional she wants to be closer to Boston’s vibrant cultural scene. And as a Newton native, she wants to be closer to her hometown as well.

Chen acknowledged that to live in the MetroWest region, she’ll need a roommate because living on her own would be unaffordable.

“It’s been a learning process, for sure,” she said.

Another panelist, Caroline Cuerva, works in marketing at Good Shepherd Community Care in Newton and wasn’t able to live with her family after college.

She and her boyfriend moved into a small apartment in Brighton and later rented in Chestnut Hill. After they got engaged, they decided to buy a home.

“We decided, let’s look local—Newton, Needham, Watertown—we’ll find a small condo or something,” Cuerva said with an eyeroll, met with a thunderous laughter from the audience.

Cuerva said they “lucked out” finding a condo in Medfield, about a half-hour drive from Newton, and they only got that condo because a previous offer had fallen through.

“If we’re looking to start a family in a few years, there’s definitely no way that we’ll be able to stay in our current property with the size that it is,” Cuerva said. “But there is just no realm of possibility of affording a single-family house with a yard in this area at this time, so it could potentially mean leaving the state somewhere down the line.”

According to Redfin, the median home price in Middlesex County is around $755,000. In Newton, it’s around $1.4 million.

And according to Zillow, median rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in Newton is $2,500.

What can be done?

Fellow panelist William Ferreira said several of his closest friends have done just that—moved away from Massachusetts due to housing costs—despite having college degrees and jobs that pay well.

“They don’t want to have to commute from two hours away so they can finally get a place,” he said.

Ferreira himself moved away for a while, too, to the Midwest, before moving back to Massachusetts with his wife for work.

But what’s to be done about it all?

The state legislature passed the MBTA Communities Act a few years ago, and most communities required to comply have done so, including Newton, by rezoning neighborhoods near MBTA stops for higher density housing.

Gov. Maura Healey recently signed the largest housing bond bill in state history, and she wants to see hundreds of thousands of housing units built in the next few years to alleviate demand.

Ferreira mentioned Japan, which has some of the lowest housing costs in the world, and said that country doesn’t impede housing development with inflexible zoning.

“They allow things to be built within certain parameters that usually have to do with how much noise or disturbance they make,” he explained. “So you can have a multi-family next to a single-family next a little corner market or bakery, which not only makes it more vibrant and more interesting, but makes it easier to build.”

The second panel consisted of planning directors from Newton, Wellesely, Watertown and Needham. And the general consensus of that panel agreed with Ferreira, that more housing and less stringent zoning were needed to address the housing cost crisis.

Newton Planning Director Barney Heath mentioned the contentious Village Center Overlay District battle as a step toward opening opportunities for more housing near public transportation.

“I’m really pleased about that, and I’m hoping good things come from that,” he said. “I think there was a lot of compromise and good thinking that went into that, and there’s a whole unknown process about what that is going to produce and whether it’s going to be something that the community embraces.”

Heath also referenced a Boston Globe article about Austin, Texas, making so much progress with its housing stock.

“I hate when Texas beats Boston or New England in anything, but it sounds like they’re really kicking our butts in terms of housing,” Heath mused.

Wellesley Planning Director Eric Arbeene talked about his town’s Strategic Housing Plan, and Wellesley will have results of public feedback on that plan soon. That town is forecast to see its population drop by about 15 percent in the next several years because young families aren’t moving there.

Public support has been a hurdle everywhere. Newton voters ousted several city councilors who had supported the Village Center Overlay District rezoning. And Needham, which passed a robust housing plan at its Town Meeting, is set to have that plan put to a referendum in January.

And thus, the state is poised to deem that town non-compliant with the MBTA Communities Act next month.

“I think it’s hard for people to wrap their heads around the consequences of it, to be honest with you,” Heath said about the housing crisis and opposition to development. “Some people might think that it’s a good thing to lose population—they think, ‘easier for me to get around,’—so I think the results have to be tangible for people.”

Heath suggested people look at the impacts the crisis has on schools, because if student population drops, communities will have to close schools.

He ended with an Olympics analogy.

“I think, hearing from Doug [Howgate], we’re kind of in the Olympics right now, and we’re not looking too good in terms of state competitiveness,” Heath said. “So we need to really up our game.”

You can watch the entire forum online.