StateHouse

Massachusetts State House. Wikimedia Commons photo

The following first appeared in Commonwealth Beacon.

By Paul DeBole

DOES ANYONE ever wake up in the morning and think to themselves, “I am going to be unreasonable today?” Of course not or, at least thankfully, not very many. Is the City of Newton out to deny a fair wage to their public school teachers? I can answer in all honesty, no. Are the teachers being unreasonable in their demands for new and better contract terms to keep pace with the relatively high rate of inflation that we have seen over the past few years — 4.7 percent in 2021, 8 percent in 2022, and 4.1 percent in 2023? The answer again is a resounding no.

The mission of local government is to provide necessary services to its residents. Just think of all of the day-to-day, quality of life services that are provided by municipal governments: libraries, police and fire protection, public education, ambulance services, and recreation programs are just a few. When I turn on my water faucet, I take it for granted that clean, wonderfully tasting water will come out, but it is the municipality that maintains the miles upon miles of piping in its water distribution system that provides that drinking water to all of us.

Municipal government is the one level of government that is closest to the people it serves, but it is the most limited in terms of the way that it can develop a revenue stream to finance its operations. The funding method that municipalities employ to provide these services are ad valorem taxes, which are taxes based on the value of an item. Specifically, real estate taxes and motor vehicle excise taxes.

There has always been some level or type of real estate taxation, but that system is not based on the taxpayer’s ability to pay (as in the federal or state income tax), but rather the perceived value of the asset. This method was formalized in our legal system by William the Conqueror in the year 1085. In the year 1066, following his victory over King Harold at the Battle of Hastings and his subsequent ascension to the throne, one of his first actions was to send out his sheriffs and knights to record the names of all residents of the realm and to list, in detail, what property they possessed. The list included everything from farmland, woodland, and pasture owned chickens, cows, and sheep.

The results of that survey were memorialized in The Domesday Book (my apologies for the uncomfortable flashback to your Westen Civ course in college). Using that listing, an annual tax was assessed by the crown. In essence, that is exactly the type of property taxation that we have here in Massachusetts, and indeed in most of the country, in 2024. That same method has been kicking around for almost 1,000 years.

One might think that it’s time to consider a better method.

In Massachusetts, we have a further impediment to that process called Proposition 2½, which at its most basic level means that — absent a major real estate development project in the municipality, a new revenue source, a hefty increase in state aid, or a huge increase in property valuation – the most that the real estate tax levy will increase between Year 1 and Year 2 is 2 ½ percent.

What does that mean for the municipality? It means that the amount of additional revenues that it can use to cover any increases in its labor costs is limited as well.

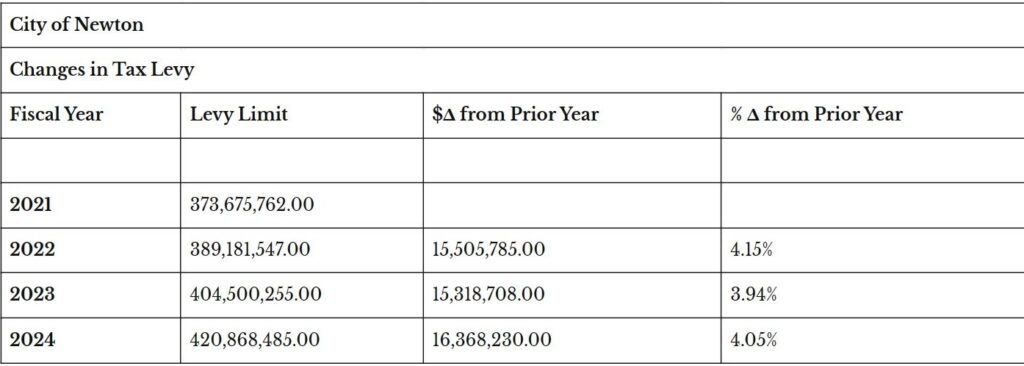

If we look at the increases in Newton’s tax levy as calculated by the Massachusetts Department of Revenue, which tries to take these variables into account, we see about a 4 percent increase in revenue on average.

Assuming all other costs remain equal, because we all know that fuel costs, health insurance costs, electricity costs, and, of course, pension liabilities, never (sarcasm) increase, then how can a municipal official ever vote for a collective bargaining agreement which raises labor costs by an amount even close to that 4 percent number?

And almost every elected official will tell you that they recognize that they need to compensate their employees fairly and to try to keep pace with inflation. It is not a case of an unwillingness on the part of elected officials to agree to increases in compensation for its valuable employees, but an inability to do so.

Newton and communities like it need to look at the way they finance municipal government operations and at least look at some possible alternatives. For that to happen, local government officials and public sector labor unions need to work hand in hand with the Legislature to explore the nature and scope of the problem; and, hopefully, develop alternatives to our antiquated system of financing local government operations.

Paul DeBole is an assistant professor of justice studies at Lasell University in Newton.