franklinschool020323

The Franklin School. Photo by Dan Atkinson

Newton is just a few years away from a housing turnover that could dramatically change the city’s make-up and replenish enrollment in its schools, according to Dr. Jerome McKibben of McKibben Demographic Research.

McKibben presented results of a study of Newton’s emerging demographics to the Newton School Committee Monday night, giving a glimpse into the city’s population and a forecast of student enrollment in the coming years.

McKibben used census data, migration rates, IRS data, housing market numbers and more to shape a Newton-specific forecast.

Here are a few takeaways:

Moving in

The forecast, for example, assumes Newton will have 60 new homes built per year over the next 10 years.

“The district added about 500 housing units last decade, so we’re kind of assuming you’re maintaining that growth rate,” McKibben said. “More importantly, though, the district will have 1,100 existing homes per year.”

Home sales mean moving families, which impacts school enrollment.

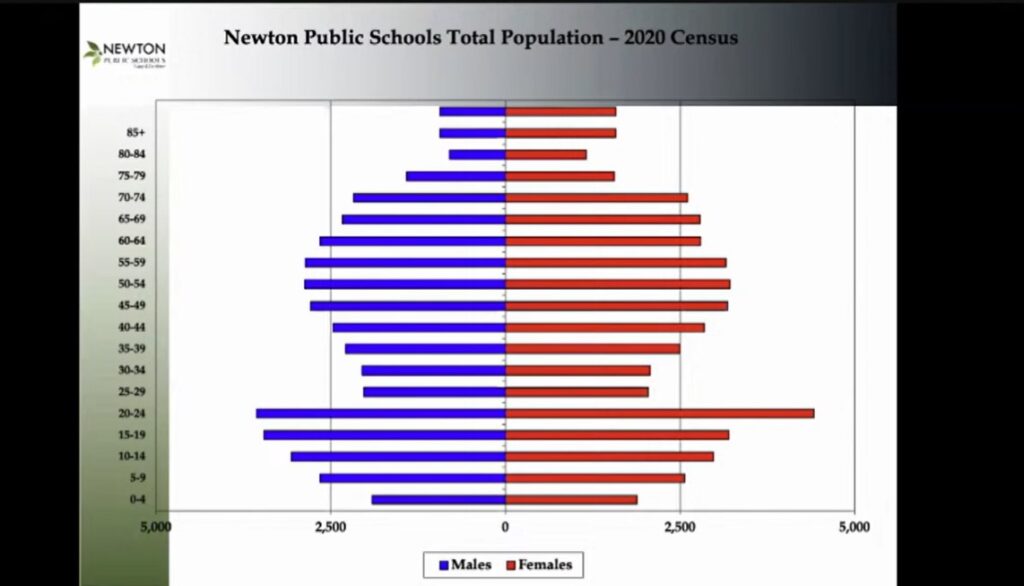

The biggest factor in predicting population trends is found in age structure—how the population is spread across different ages—and which age groups have the largest numbers.

Newton’s population is biggest in the 35-to-39-year-old group, with the 40-to-44 group in a close second place, and the 30-to-34 age group is in third.

Around 80 percent of births occur with women ages 20 to 24, McKibben noted. And ages 35 to 44 is when most people have kids in schools.

“When you see changes in the number of births in an area from year to year, it’s not so much change in the birth rate but changes in the number of women of prime child-bearing age,” McKibben said.

For their forecasting, McKibben added, his team removes college-aged populations out because college-aged young people tend to move around and not have kids yet.

“When you have public board meetings, the vast majority of the people in the audience are going to be between the ages of 35 and 54,” he said.

Moving out

According to the 2020 census, Newton’s largest over-25 population is in the 50-to-59 age range.

People in their 50s tend to have older kids who have graduated from high school already. Those parents are often called “empty nesters,” but they don’t tend to move out of their homes until later.

“That’s why your enrollment peaked about 2017 and started dropping off, because you had more and more households empty-nesting,” McKibben said.

But another large age group in Newton in that census consisted of people in their late-60s and early 70s, and that signals a population turnover.

The number of Newtonians aging into their 70s and 80s in the next decade is huge, and that’s the age bracket in which most people tend to sell their homes and downsize to condos and retirement homes.

“The rate of that increase of households over 70 is going to be going up faster than your number of empty-nesters,” McKibben explained. “So the turnover will become the prominent driving demographic factor, not empty-nesting, going forward.”

The Baby Boomers

The Baby Boom generation—born between 1946 and 1964—is aging. The peak of that baby boom, which happened around 1957, is 67 years old. The front end—the start of the Baby Boom, is approaching 80.

“If you go forward ten years, the peak will be 77 and the front end will be 87,” McKibben said. “They’re either going to start dying or downsizing, one of the two.”

The result will be a bunch of houses with school-aged kids living in them for the first time in 30 years.

Owning vs. renting

Homeowners tend to stay in a community much longer than renters, McKibben said.

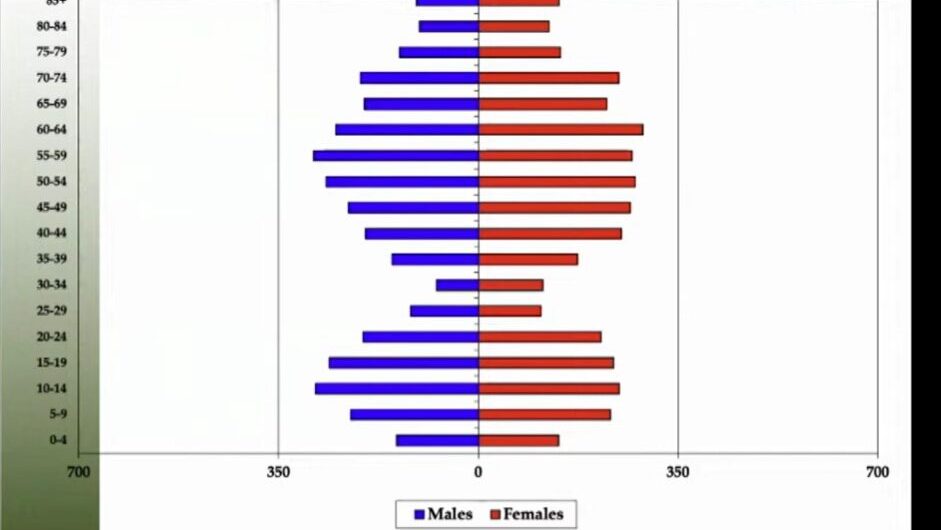

As an example, Lincoln-Eliot Elementary School has more rental units near it than any of the other elementary schools. So a lot of families with kids in that school are renting their homes.

There are a lot of adults between 25 and 40 in that area, but there aren’t a lot of kids in that between 0 and 9 years old, signifying that the Lincoln-Eliot neighborhoods may just be where a lot of young professionals live.

Memorial-Spaulding Elementary School, however, is in an area with the most homeownership. But there’s a very low population under the age of 5.

“So this area, unless there’s building going on, you’re going to see a reduction in enrollment unless a lot of these homes start turning over at a high enough number,” McKibben said.

And a dozen or so home sales won’t get the job done, he added.

“It’s gotta be 40-to-50 a year, bringing in young families with school-aged, and more importantly, preschool-aged kids, to build that cohort back up,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons why you had a transition in the last decade. You had large cohorts with preschool kids aging in and a lot of growth and migration, and now they’re aging out.”

About a third of Newton’s population is over age 65, McKibben noted, signaling a population transition on the horizon.

Will that turnover mean more affordable housing in Newton?

“There’s no such thing as affordable housing in New England, so that takes care of that,” McKibben answered bluntly.

School enrollment

McKibben’s forecast says Newton’s schools will see a decline in enrollment until the end of the decade.

“If I got a bucket of water and I’m pouring water in the top and there’s a hole in the bottom, as long as I’m pouring in faster than it’s going out the bottom, the level will go up,” McKibben said. “But if for some reason the whole in the bottom gets bigger and it’s going out faster than I’m pouring in, if I keep pouring at the same rate the level will drop.”

School enrollment works similarly, factoring the size of the cohort (group of kids in the same grade) entering the school system in kindergarten vs. the number of kids aging out of the school system after high school.

Newton has had a “wave” of smaller student population going through its system in the last seven years.

As more households have turned over, more families with young kids have moved in, but not enough to offset the number of students graduating.

That’s set to change as that wave of smaller cohorts moves through and graduates and is replaced by a more stable population.

“After 2030, then the cohorts will rebalance out and you’ll start to see some growth afterward,” McKibben said.

The MBTA Communities Act

School Committee member Paul Levy asked McKibben why he didn’t include the 8.300 units of housing the city re-zoned to meet its MBTA Communities Act requirement, if city and state officials are expecting those housing units to be built.

That number won’t happen, McKibben answered. Those numbers aren’t real.

Newton’s MBTA Communities Act uses a compliance formula to estimate how many hypothetical units a community must re-zone their MBTA neighborhoods to hypothetically fit. The formula uses small unit sizes and an assumption of fresh ground to build on in its calculations. And the only people insisting that number would be built out were city councilors and others who opposed the village center rezoning plan.

Because some of the rezoning includes lots that have protected buildings (like historic churches) and because Newton is already completely developed, there isn’t enough room to build 8,300 housing units without tearing apart large parts of the city to make it happen.

Those city councilors were corrected by Planning Department officials before the vote to approve the rezoning proposal even happened.

Building 8,300 housing units would increase the city’s housing stock by 25 percent, which just doesn’t happen.

“Not even Texas pulls that off, where they’re building to beat the band,” McKibben quipped. “That’s such an unrealistic assumption that I would put it on par with paying off the national debt by the end of the decade, the probability of that happening.”

McKibben’s presentation can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube.

EDITOR’S NOTE: An earlier version of this story had Dr. McKibben’s name spelled as “McGibbon” near the top. That has been corrected.